Every little thing We As soon as Believed In

I didn’t get up as we speak pondering I might write a thank-you to The Atlantichowever after studying David Brooks’s “Every little thing We As soon as Believed In,” I really feel compelled. For thus lengthy, I’ve felt the ache and embarrassment of seeing my nation forsake its honor whereas the general public I used to see as political allies cheered—however I’ve by no means been in a position to specific it adequately. Brooks put my emotions to phrases. His article offers me hope that our nation can and certain shall be made stronger over time.

Tom Dornish

Lincoln, Neb.

I all the time stay up for David Brooks’s articles and sometimes agree with a lot of what he writes. Nevertheless, his continued lionization of the Reagan administration—and Ronald Reagan himself—strikes me as an odd blind spot.

Brooks’s critiques of progressive missteps, together with these outlined in “How the Ivy League Broke America” and reiterated in his current article, have given me a lot to mirror on. However I don’t imagine Brooks has paid enough consideration to the position the Reagan Revolution performed in undermining the American dream and weakening the working class.

Take into account Reagan’s large tax cuts, which drove a marked rise in revenue inequality. His firing of unionized air-traffic controllers dealt a serious blow to organized labor, and his divisive racial rhetoric—his use of the notorious “Welfare Queen” trope; his “States’ Rights” speech in Philadelphia, Mississippi—feels in line with the reactionaries of as we speak whom Brooks criticizes.

This doesn’t diminish the legit critiques of the left. However a fuller reckoning with Reagan’s legacy—by Brooks, particularly—would provide a extra balanced and persuasive evaluation. It may additionally assist his critique of liberal excesses land with readers who see Reagan not as a paragon of management, however as a key architect of our present inequality and division.

Adam Udell

Downingtown, Pa.

It’s not day by day {that a} public mental castigates himself for a “pathetic” lack of foresight, and David Brooks is to be counseled for doing so. I used to be struck, although, that nowhere in his dialogue of Nineteenth- and early-Twentieth-century reform actions, nor in his name for a “Whig-like working-class abundance agenda,” does he point out labor unions. As Brooks absolutely is aware of, there would by no means have been a center class in the USA if unionized staff hadn’t fought to acquire a fairer share of the fruits of their labor. I’m a proud union member at The New Yorker. Any viable “working-class abundance agenda” should acknowledge and rejoice staff’ proper to prepare within the office.

Douglas Watson

New York, N.Y.

I didn’t attend an elite college of the sort David Brooks describes till graduate college. However I by no means skilled something that will have ignited the bitterness that Brooks diagnoses within the reactionaries. I don’t suppose it’s honest in charge universities for our present political predicament. My higher-education experiences promoted moral conduct and instilled in me a dedication to serve society with the data I gained.

Barbara Okay. Sullivan-Watts

Kingston, R.I.

David Brooks’s “Every little thing We As soon as Believed In” was attribute of all his work: insightful, and chastening however hopeful. I want I shared his optimism that conservatism could but discover its manner again.

I feel Brooks could misunderstand the ascendant proper. Though he accurately recognized its supply within the snark of The Dartmouth Evaluationthe ascendant proper is something however reactionary—it’s triumphalist. Triumphalism is the kissing cousin of nihilism. These of us who joined the conservative motion within the late ’70s and early ’80s had learn our Edmund Burke too effectively to think about conservatism sweeping away all earlier than it to ascertain a conservative utopia. Certainly, we have been conservatives exactly as a result of we believed there was no such factor: Right here we now have no abiding metropolis. We have been a definite minority combating an uphill battle that we may by no means really win. Those that joined the motion in the course of the second Reagan administration and later have been, I feel, extra drawn to energy for its personal sake. That’s what we’re seeing as we speak.

Brooks fails to correctly blame conservatives for the rise of this triumphalist proper. Conservatism is institutionalist, however the one establishment we uncared for within the ’90s was a very powerful of all: the household. We bought distracted by the tradition wars and ignored the financial challenges that households confronted. We have been studying Milton Friedman once we ought to have been studying Pope Leo XIII. If the triumphalist proper has seized management of conservatism, then we conservatives have solely ourselves in charge.

Stephen Danckert

Rockland, Mass.

I’m genuinely heartened by the constructive honesty in David Brooks’s mea culpa. Nonetheless, after studying by way of his article a number of instances, I’m left with the sense that he has not but completely plumbed the questions his reflections elevate.

Why didn’t Brooks see this coming? Did conservatives within the Nineteen Eighties actually suppose that reactionaries would merely pave the way in which for the conservative agenda after which permit themselves to be shunted apart? Maybe conservatives then, as now, noticed themselves as working with the lesser of two evils. To carry in regards to the civic renewal Brooks hopes for, nonetheless, they might want to absolutely separate themselves from the reactionaries and focus once more on the general public curiosity.

In 1895, an article in The Atlantic described a gaggle of politicians referred to as the “mugwumps,” who labored to free themselves from get together affiliations and centered on what was greatest for the nation, to vital impact. The mugwumps, it famous, “kind a category, by no means a big one, of individuals who possess the ability of seeing pretty the alternative sides of a query, and who lack the barnacle college of sticking tight to no matter one is connected, whether or not or not it’s the steadfast rock or the stressed keel.” If only a handful of members of Congress from each events have been prepared to behave in the same method, the rebirth Brooks hopes for would possibly really develop into a actuality.

Nicholas cost

Westport Island, Maine

I applaud David Brooks’s essay on not foreseeing the present “conservative” takeover of the nation. What I don’t share with Brooks, although, is his optimism concerning the USA’ potential to get well. Though he cites quite a few historic examples of countries that bounced again after catastrophe, there may be one variable that wasn’t current in these instances: local weather change.

The Trump administration has moved to intestine decades-old environmental laws, in addition to federal experience and oversight. It has eradicated funding for local weather motion and doubled down on fossil fuels. Which means even our present, arguably modest efforts to scale back carbon emissions are being reversed, probably making it unattainable to forestall catastrophic local weather change. As soon as this occurs, the wildfires, floods, and excessive climate of current years will look like paradise.

So whereas the USA as a democracy could ultimately get well, it would doubtless be too late for our planet.

Michael Wright

Glen Rock, Pa.

Behind the Cowl

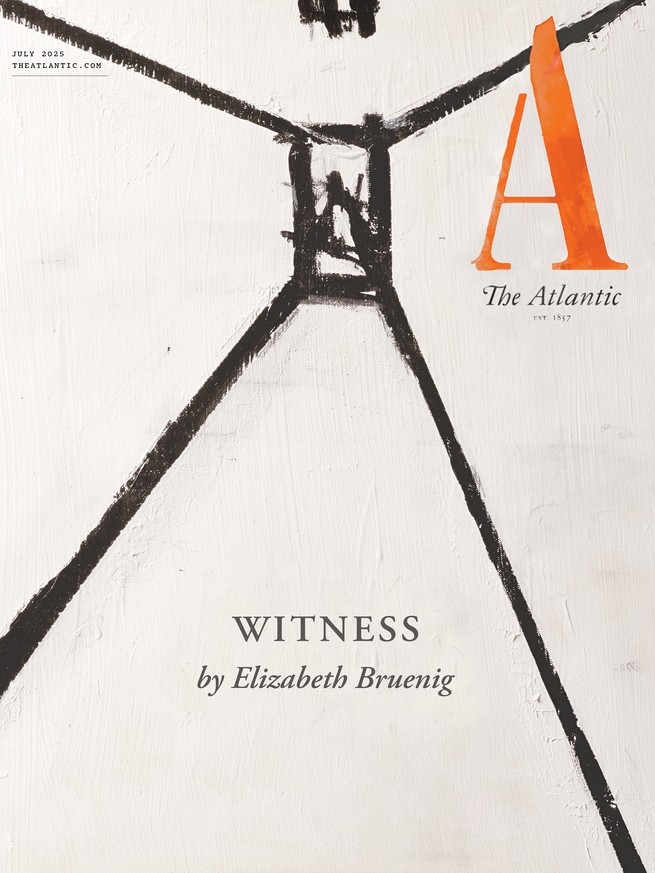

On this month’s cowl story (“Witness”), Elizabeth Bruenig describes her expertise watching executions throughout her years of reporting on the dying penalty. What she has seen has not altered her conviction that capital punishment should finish, however, as she writes, “it has modified my understanding of why.” The dying penalty guarantees justice, or a minimum of vengeance, but it surely forecloses the opportunity of mercy. For our cowl, The Atlantic’s artistic director, Peter Mendelsund, painted a picture of the hall resulting in an execution chamber, and a prisoner mendacity susceptible on the desk inside it.

— Paul Spella, Senior Artwork Director

This text seems within the July 2025 print version with the headline “The Commons.”